From an Original Picture given by herself to the Countess of Sandwich and by the present Earl of Sandwich to Mr Walpole 1757

Title: Ninon de l'Enclos and her century

Author: Mary C. Rowsell

Release date: October 24, 2023 [eBook #71953]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Brentano's, 1910

Credits: Susan Skinner, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

BY

M. C. ROWSELL

AUTHOR OF

“THE FRIEND OF THE PEOPLE,” “TRAITOR OR PATRIOT,” “THORNDYKE

MANOR,” “MONSIEUR DE PARIS,” ETC. ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BRENTANO’S

NEW YORK

HURST & BLACKETT, LIMITED

LONDON

1910

Printed in Great Britain

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I | 1 |

| Birth—Parentage—“Arms and the Man”—A Vain Hope—Contraband Novels—A Change of Educational System—Ninon’s Endowments—The Wrinkle—A Letter to M. de L’Enclos and What Came of it—A Glorious Time—“Troublesome Huguenots”—The Château at Loches, and a New Acquaintance—“When Greek meets Greek”—The Prisoners—“Liberty”—The Shades of Night—Vagabonds? or Two Young Gentlemen of Consequence?—Tired Out—A Dilemma—Ninon Herself Again—Consolation. | |

| Chapter II | 14 |

| Troublesome Huguenots—Madame de L’Enclos—An Escapade and Nurse Madeleine—Their Majesties—The Hôtel Bourgogne—The End of the Adventure—St Vincent de Paul and his Charities—Dying Paternal Counsel—Ninon’s New Home—Duelling—Richelieu and the Times. | |

| Chapter III | 27 |

| A Life-long Friend—St Evrémond’s Courtly Mot—Rabelais v. Petronius—Society and the Salons—The Golden Days—The Man in Black. | |

| Chapter IV | 36 |

| A “Delicious Person”—Voiture’s Jealousy—A Tardy Recognition—Coward Conscience—A Protestant Pope—The Hôtel de Rambouillet—St Evrémond—The Duel—Nurse Madeleine—Cloistral Seclusion and Jacques Callot—“Merry Companions Every One”—and One in Particular. | |

| Chapter V | 51 |

| An Excursion to Gentilly—“Uraniæ Sacrum”—César and Ruggieri—The rue d’Enfer and the Capucins—Perditor—The Love-philtre—Seeing the Devil—“Now You are Mine!” | |

| Chapter VI | 61 |

| Nemesis—Ninon’s Theories—Wits and Beaux of the Salons—Found at Last—“The Smart Set”—A Domestic Ménage—Scarron—The Fatal Carnival—The Bond of Ninon—Corneille and The Cid—The Cardinal’s Jealousy—Enlarging the Borders—Monsieur l’Abbé and the Capon Leg—The Grey Cardinal—A Faithful Servant. | |

| Chapter VII[vi] | 81 |

| Mélusine—Cinq-Mars—An Ill-advised Marriage—The Conspiracy—The Revenge—The Scaffold—A Cry from the Bastille—The Lady’s Man—“The Cardinal’s Hangman”—Finis—Louis’s Evensong—A Little Oversight—The King’s Nightcap—Mazarin—Ninon’s Hero. | |

| Chapter VIII | 91 |

| “Loving like a Madman”—A Great Transformation—The Unjust Tax—Parted Lovers—A Gay Court and A School for Scandal, and Mazarin’s Policy—The Regent’s Caprices—The King’s Upholsterer’s Young Son—The Théâtre Illustre—The Company of Monsieur and Molière. | |

| Chapter IX | 103 |

| The Rift in the Lute—In the Vexin—The Miracle of the Gardener’s Cottage—Italian Opera in Paris—Parted Lovers—“Ninum”—Scarron and Françoise d’Aubigné—Treachery—A Journey to Naples—Masaniello—Renewing Acquaintances—Mazarin’s Mandate. | |

| Chapter X | 115 |

| The Fronde and Mazarin—A Brittany Manor—Borrowed Locks—The Flight to St Germains—A Gouty Duke—Across the Channel—The Evil Genius—The Scaffold at Whitehall—Starving in the Louvre—The Mazarinade—Poverty—Condé’s Indignation—The Cannon of the Bastille—The Young King. | |

| Chapter XI | 124 |

| Invalids in the rue des Tournelles—On the Battlements—“La Grande Mademoiselle”—Casting Lots—The Sacrifice—The Bag of Gold—“Get Thee to a Convent”—The Battle of the Sonnets—A Curl-paper—The Triumph and Defeat of Bacchus—A Secret Door—Cross Questions and Crooked Answers—The Youthful Autocrat. | |

| Chapter XII | 135 |

| The Whirligig of Time, and an Old Friend—Going to the Fair—A Terrible Experience—The Young Abbé—“The Brigands of La Trappe”—The New Ordering—An Enduring Memory—The King over the Water—Unfulfilled Aspirations—“Not Good-looking.” | |

| Chapter XIII | 144 |

| Christina’s Modes and Robes—Encumbering Favour—A Comedy at the Petit-Bourbon—The Liberty of the Queen and the Liberty of the Subject—Tears and Absolutions—The Tragedy in the Galérie des Cerfs—Disillusions. | |

| Chapter XIV | 154 |

| Les Précieuses Ridicules—Sappho and Le Grand Cyrus—The Poets of the Latin Quarter—The Satire which Kills—A Lost Child—Periwigs and New Modes—The Royal Marriage and a Grand Entry. | |

| Chapter XV[vii] | 163 |

| Réunions—The Scarrons—The Fête at Vaux—The Little Old Man in the Dressing-gown—Louise de la Vallière—How the Mice Play when the Cat’s Away—“Pauvre Scarron”—An Atrocious Crime. | |

| Chapter XVI | 175 |

| A Lettre de Cachet—Mazarin’s Dying Counsel—Madame Scarron Continues to Receive—Fouquet’s Intentions and What Came of Them—The Squirrel and the Snake—The Man in the Iron Mask—An Incommoding Admirer—“Calice cher, ou le parfum n’est plus”—The Roses’ Sepulchre. | |

| Chapter XVII | 185 |

| A Fashionable Water-cure Resort—M. de Roquelaure and his Friends—Louis le Grand—“A Favourite with the Ladies”—The Broken Sword—A Billet-doux—La Vallière and la Montespan—The Rebukes from the Pulpit—Putting to the Test—Le Tartufe—The Triumphs of Molière—The Story of Clotilde. | |

| Chapter XVIII | 199 |

| A Disastrous Wooing—Fénelon—“Mademoiselle de L’Enclos”—The Pride that had a Fall—The Death of the Duchesse d’Orléans—Intrigue—The Sun-King and the Shadows—The Clermont Scholar’s Crime—Monsieur de Montespan—Tardy Indignation—The Encounter—The Filles Répenties—What the Cards Foretold. | |

| Chapter XIX | 212 |

| “In Durance Vile”—Molière’s Mot—The Malade Imaginaire—“Rogues and Vagabonds”—The Passing of Molière—The Narrowing Circle—Fontenelle—Lulli—Racine—The Little Marquis—A Tardy Pardon—The Charming Widow Scarron—A Journey to the Vosges, and the Haunted Chamber. | |

| Chapter XX | 228 |

| The Crime of Madame Tiquet—A Charming Little Hand—Aqua Toffana—The Casket—A Devout Criminal—The Sinner and the Saint—Monsieur de Lauzun’s Boots—“Sister Louise”—La Fontange—“Madame de Maintenant”—The Blanks in the Circle—The Vatican Fishes and their Good Example—Piety at Versailles—The Periwigs and the Paniers—Père la Chaise—A Dull Court—Monsieur de St Evrémond’s Decision. | |

| Chapter XXI | 241 |

| A Distinguished Salon—The Duke’s Homage—Quietism—The Disastrous Edict—The Writing on the Window-pane—The Persecution of the Huguenots—The Pamphleteers—The Story of Jean Larcher and The Ghost of M. Scarron—The Two Policies. | |

| Chapter XXII[viii] | 251 |

| Mademoiselle de L’Enclos’ Cercle—Madeleine de Scudéri—The Abbé Dubois—“The French Calliope,” and the Romance of her Life—“Revenons à nos Moutons”—A Resurrection?—Racine and his Detractors—“Esther”—Athalie and St Cyr—Madame Guyon and the Quietists. | |

| Chapter XXIII | 263 |

| A Grave Question—The Troublesome Brother-in-Law—“No Vocation”—The Duke’s Choice—Peace for “La Grande Mademoiselle”—An Invitation to Versailles—Behind the Arras—Between the Alternatives—D’Aubigné’s Shadow—A Broken Friendship. | |

| Chapter XXIV | 275 |

| The Falling of the Leaves—Gallican Rights—“The Eagle of Meaux”—Condé’s Funeral Oration—The Abbé Gedouin’s Theory—A Bag of Bones—Marriage and Sugar-plums—The Valour of Monsieur du Maine—The King’s Repentance—The next Campaign—La Fontaine and Madame de Sablière—MM. de Port Royal—The Fate of Madame Guyon—“Mademoiselle Balbien.” | |

| Chapter XXV | 288 |

| The Melancholy King—The Portents of the Storm—The Ambition of Madame Louise Quatorze—The Farrier of Provence—The Ghost in the Wood—Ninon’s Objection—The King’s Conscience—A Dreary Court—Racine’s Slip of the Tongue—The Passing of a Great Poet, and a Busy Pen Laid Down. | |

| Chapter XXVI | 301 |

| Leaving the Old Home—“Wrinkles”—Young Years and Old Friends—“A Bad Cook and a Little Bit of Hot Coal”—Voltaire—Irène—Making a Library—“Adieu, Mes Amis”—The Man in Black. |

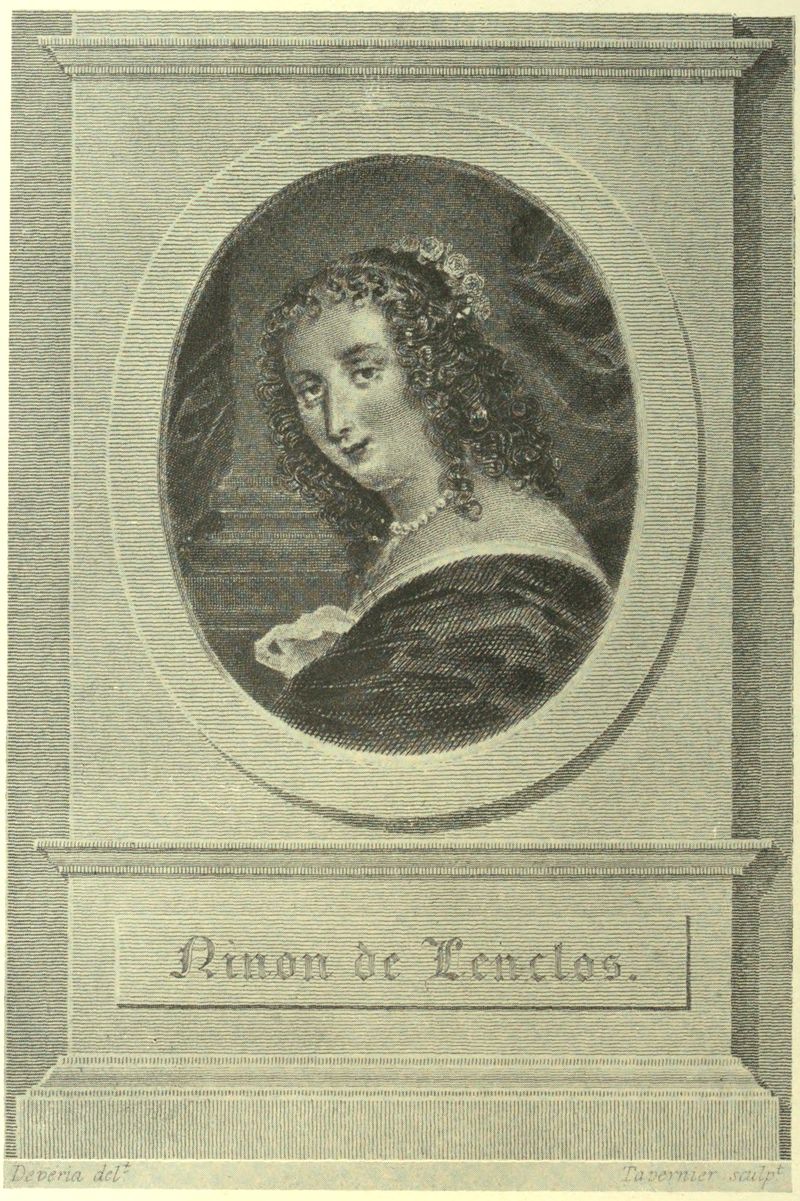

| Ninon de L’Enclos | Frontispiece | |

| Cardinal Richelieu | To face page | 24 |

| De la Rochefoucauld | ” | 48 |

| Molière | ” | 100 |

| St Evrémond | ” | 112 |

| Ninon de L’Enclos | ” | 127 |

NINON DE L’ENCLOS

AND HER CENTURY

NINON DE L’ENCLOS

AND HER CENTURY

Birth—Parentage—“Arms and the Man”—A Vain Hope—Contraband Novels—A Change of Educational System—Ninon’s Endowments—The Wrinkle—A Letter to M. de L’Enclos and What Came of it—A Glorious Time—“Troublesome Huguenots”—The Château at Loches, and a New Acquaintance—“When Greek meets Greek”—The Prisoners—“Liberty”—The Shades of Night—Vagabonds? or Two Young Gentlemen of Consequence?—Tired Out—A Dilemma—Ninon Herself Again—Consolation.

Anne de L’Enclos was born in Paris in 1615. She was the daughter of Monsieur de L’Enclos, a gentleman of Touraine, and of his wife, a member of the family of the Abra de Raconis of the Orléanois.

It would not be easy to find characteristics more diverse than those distinguishing this pair. Their union was an alliance arranged for them—a mariage de convenance. Diametrically opposite in temperament, Monsieur was handsome and distinguished-looking; while the face and figure of Madame were ordinary. She was constitutionally timid, and intellectually narrow, devoted to asceticism, and reserved in manner. She passed her time in seclusion, dividing it between charitable works, the reading of pious books, and attendance at Mass and the other services of the Church. Monsieur de L’Enclos, on the other hand, was a votary of[2] every pleasure and delightful distraction the world could afford him. Among them he counted duelling; he was a skilled swordsman, and his rapier play was of the finest. A brave and gallant soldier, he had served the royal cause during the later years of Henri IV., and so on into the reign of Louis XIII. He was a bon vivant, and arms and intrigue, which were as the breath of life to him, he sought after wherever the choicest opportunities of those were likely to be found.

Notwithstanding, the rule of life-long bickering and mutual reproach attending such ill-assorted unions, would seem to be proved by its exception in the case of Ninon’s parents; since no record of any such domestic strife stands against them. Bearing and forbearing, they agreed to differ, and went their several ways—Madame de L’Enclos undertaking the training and instruction of Ninon in those earliest years, in the fond hope that there would be a day when she should take the veil and become a nun. Before, however, she attained to the years of as much discretion as she ever possessed, she had arrived at the standpoint of the way she intended to take of the life before her, which was to roll into years that did not end until the dawning of the eighteenth century; and it in no way included any such intention. So sturdily opposed to it, indeed, was she, that it irresistibly suggests the possibility of her being the inspiration of the old song—“Ninon wouldn’t be a nun”—

For Ninon was her father’s child; almost all her inherited instincts were from him. The endeavours of Madame de L’Enclos failed disastrously. The monotony and rigid routine of the young girl’s life repelled the bright, frank spirit, and drove it to opposite extreme, resulting in sentiments of disgust for the pious observances of her church; and taken there under compulsion day in, day out, she usually contrived to substitute some plump little volume of romance, or other light literature, at the function, for her Mass-book and breviary, to while away the tedium.

In no very long time Monsieur de L’Enclos, noting the bent of his daughter’s nature, himself took over her training. He carried it on, it is scarcely necessary to say, upon a plane widely apart from the mother’s. A man of refined intellect, he had studied the books and philosophy of the renaissance of literature; and before Ninon was eleven years old, while imbuing her with the love of reading such books as the essays of Montaigne and the works of Charon, he accustomed her to think and to reason for herself, an art of which she very soon became a past-mistress, the result being an ardent recognition of the law of liberty, and the Franciscan counsel of perfection: “Fay ce qu’et voudray.” Ninon possessed an excellent gift of tongues, cultivating it to the extent of acquiring fluently, Italian, Spanish, and English, rendered the more easy of mastery from her knowledge of Latin, which she so frequently quotes in her correspondence.

Her love of music was great; she sang well,[4] and was a proficient on the lute, in which her father himself, a fine player, instructed her. She conversed with facility, and doubtless took care to cultivate her natural gifts in those days when the arts of conversation and causerie were indispensable for shining in society, and she loved to tell a good story; but she drew a distinct line at reciting. One day when Mignard, the painter, deplored his handsome daughter’s defective memory, she consoled him—“How fortunate you are,” she said, “she cannot recite.”

The popular acceptation of Ninon de L’Enclos’ claims to celebrity would appear to be her beauty, which she retained to almost the end of her long life—a beauty that was notable; but it lay less in perfection of the contours of her face, than in the glorious freshness of her complexion, and the expression of her magnificent eyes, at once vivacious and sympathetic, gentle and modest-glancing, yet brilliant with voluptuous languor. Any defects of feature were probably those which crowned their grace—and when as in the matter of a slight wrinkle, which in advanced years she said had rudely planted itself on her forehead, the courtly comment on this of Monsieur de St Evrémond was to the effect that “Love had placed it there to nestle in.” Her well-proportioned figure was a little above middle height, and her dancing was infinitely graceful.

Provincial by descent, Mademoiselle de L’Enclos was a born Parisian, in that word’s every sense. Her bright eyes first opened in a small[5] house lying within the shadows of Notre-Dame, the old Cité itself, the heart of hearts of Paris, still at that time fair with green spaces and leafy hedgerows, though these were to endure only a few years longer. Her occasionally uttered wish that she had been born a man, hardly calls for grave consideration. The desire to don masculine garments and to ride and fence and shoot, and to indulge generally in manly pursuits, occurred to her when she was still short of twelve years old, by which time she was able to write well; and her earliest epistolary correspondence included a letter addressed to her father. It ran as follows:—

“My Very Honoured Father,—I am eleven years old. I am big and strong; but I shall certainly fall ill, if I continue to assist at three masses every day, especially on account of one performed by a great, gouty, fat canon, who takes at least twelve minutes to get through the Epistle and the Gospel, and whom the choir boys are obliged to put back again on his feet after each genuflexion. I would as soon see one of the towers of Notre Dame on the altar-steps; they would move quite as quickly, and not keep me so long from breakfast. This is not at all cheering I can tell you. In the interest of the health of your only child, it is time to put an end to this state of things. But in what manner, you will ask, and how is it to be set about? Nothing more simple. Let us suppose that instead of me, Heaven had given you a son: I should have been brought up by you, and not by my mother; already you would have begun to instruct me in arms, and mounted me on horseback, which would have much better pleased me than twiddling along the beads of a rosary to Aves, Paters, and Credos. The present moment is the one for me to inform you that I decide to be no longer a girl, and to become a boy.

“Will you therefore arrange to send for me to come to you, in order to give me an education suitable to my new sex? I am with respect, my very honoured father,—Your little

Ninon.”

This missive, which Ninon contrived to get posted without her mother’s knowledge, met with her father’s hearty approval. No more time was lost than it took to make her a handsome suit of clothes, of the latest mode, the one bearing the palm for grace and picturesqueness, far and away from all the fashions of men’s attire, speaking for itself in the canvases of Vandyck; and Ninon stands forth in the gallant bravery of silken doublet, with large loose sleeves slashed to the shoulder; her collar a falling band of richest point lace; the short velvet cloak hanging to the shoulder; the fringed breeches meeting the wide-topped boots frilled about with fine lawn; the plumed, broad-brimmed Flemish beaver hat, well-cocked to one side upon the graceful head, covered with waves of dark hair falling to the neck; gauntleted gloves of Spanish leather; her rapier hanging from the richly-embroidered baldric crossing down from the right shoulder—a picture that thrilled the heart of Monsieur de L’Enclos with ecstasy; and when, splendidly mounted, she rode forth, ruffling it gallantly beside him, he was the proud recipient of many a compliment and encomium on the son of whose existence until now nobody had been as much as aware.

These delightful days were destined, however, to come quickly to an end. Fresh disturbances arose with the Huguenots of La Rochelle and Loudun,[7] and Monsieur de L’Enclos was summoned to join his regiment. Ninon would doubtless have liked of all things to go with him; but while this was impossible, she was spared the dreaded alternative of the fat canon and the three Masses a day, by her father accepting for her an invitation from his sister, the Baroness Montaigu, who lived on her estate near Loches, on the borders of the Indre. This lady, a widow and childless, had long been desirous of making the acquaintance of her young niece, and on his way north-west, Monsieur de L’Enclos left Ninon at the château. “And when we have settled these wretched Huguenots,” said Monsieur de L’Enclos, as he bade her farewell, and slipped a double louis into her hands, “I will return for you.”

Madame de Montaigu was a charming lady, of the same spirited, gay temperament as her brother. She received her niece with the utmost kindness, and having been initiated into the girl’s whim for playing the boy, she laughingly fell in with it, and addressed her with the greatest gravity as “my pretty nephew,” introducing to her, a—shall it be said?—another young gentleman, by name François de la Rochefoucauld, Prince de Marsillac, the son of her intimate friend, the Duchesse de la Rochefoucauld. The lad was a pupil at the celebrated Jesuits’ College of La Flêche, founded by Henri IV., and usually spent part of his holidays at the Loches château.

A year or two older than Ninon, Marsillac was a shy and retiring boy, and at first rather shrank from his robustious new companion, who, however,[8] soon contrived to draw him out, putting him on his mettle by pretending to doubt his prowess with sword and rapier, and his skill generally in the noble art of fencing. She challenged him to measure weapons with her, and piqued at the idea of one younger than himself pretending to martial superiority, he cast aside his shyness, and the two falling on guard, clashed and clattered their steel in the galleries and chambers of the house, from morning till night, until the noise grew intolerable, and their weapons were taken away from them, in the fond hope of securing peace and quietness. It was, however, only partially realised; since the enforced idleness of Ninon’s hands suggested the surreptitious annexing of the head forester’s gun, with which she took aim at the blackbirds in the park avenues, and the young does in the forest: and then, seeking further variety, the two manned the pleasure-boat on the lake, and fared into such perilous places, that the voyages became strictly tabooed, and the boat was hidden away.

The constant tintamarre of the pair frequently brought its punishment; and one day, on the occasion of a too outrageous disturbance, they were locked into the library. Books they had no particular mind for that glorious sunshiny morning; still less enjoyable was the prospect of the promised dinner of dry bread and water, and they sat gloomily gazing upon the softly-waving boughs of the trees, and up through the open window into the free blue sky. Being some eighteen feet from the ground, it had not been thought necessary to bar the casement beyond[9] possibility of their trying to escape. The feat would assuredly not so much as suggest itself. Nevertheless, the temptation crept into the soul of Ninon, and she quickly imparted it to Marsillac.

Looking down, they saw that soft green turf belted the base of the wall, and taking hurried counsel, they climbed to the window-sill, and at the risk of their necks, clutching by the carved stonework, and the stout old ivy trails with which it was mantled, they dropped to the ground, and then away they hied by the clipped yew alleys, mercilessly trampling the parterres—away till they found themselves in the forest. Free now as the sweet breeze playing in their hair, they ran on, pranking and shouting, now following the little beaten tracks, now bounding over the brushwood, heedless of the rents and scratches of the thorny tangles; until after some hours, Marsillac’s pace began to drag, and very soon he said he was tired.

“That is no matter,” said Ninon, “we will hire a carriage at the first place we come to”; but the name of that place was not even to be guessed at; inasmuch as they had not the least notion which way they had taken. The great thing was to arrive at last at Tours, where Ninon said they could at once enlist as soldiers. Marsillac was, however, tired—very tired; his legs ached, and he sat down for a little rest, observing rather crossly, in the cynical way which sometimes he had, that talking was all very well; but for one thing they were not big enough for soldiers, and for another, you could not have a carriage without paying for it.

“Of course not,” acquiesced Ninon, proudly producing her double louis. “Can I not pay?” But the hours passed, the sun declined, and not so much as a solitary cottage had presented itself to their eyes, into which a shade of anxiety had crept; and ere long they began to feel certain they saw wolves and lions and bandits lurking in all directions behind the huge black forest tree-trunks, and young Monsieur de la Rochefoucauld had now grown so tired that, he wanted nothing so much as to go to bed. Even supper was a secondary consideration. Still, desperately hungry as they both were, liberty is such a glorious thing; and were they not free?—free as the air that was growing so chilly, and the pale moonlight rays as they broke through some darkening clouds, seemed to make it almost shuddery. These, however, suddenly crossed something white, and though terrifying for the moment, the second glance to which they schooled themselves brought reassurance. The white patch they saw was a bit of a cottage wall pierced by a little lattice, through which gleamed the yellow light of a tallow candle; for the two, creeping close to the panes, peeped in. But noiselessly as they strove to render their movements, the attention of a couple of big dogs of the boule-dogue breed was aroused, to the extent of one of them fastening upon Marsillac’s haut-de-chausses, and he was only induced to forbear and drop off, under the knotty, chastising stick of a man, apparently the master of the house, who turned upon the trembling truants, and bade them clear off for the vagabonds they were. Their mud-stained and torn[11] apparel, rendered more dilapidated in Marsillac’s case, by the dog’s teeth, justified to a great extent the man’s conclusions; but on their asseverating that they were not good-for-nothing at all; but two very well-born young gentlemen who had lost their way, and would be glad to pay generously for a supper, he called his wife, and committing them to her care, bade her entertain them with the best her larder afforded, and to put a bottle of good wine on the table. Then he went out, while an excellent little piece of a haunch of roe-deer—cooking apparently for the supper of the worthy couple themselves—which Dame Jacqueline set before the hungry wanderers, was heartily appreciated by both. Washed down by a glass or two of the fairly good wine, Marsillac grew hopelessly drowsy. Tired out, he wanted to go to bed. “And why not?” said the dame, not without a gleam of malice in her eyes, which had been keenly measuring the two—“but I have only one bed to offer you, our own, and you must make the best of it.” She smiled on.

“Not I,” said Ninon, rising from the settle like a giant refreshed—“I am going on to Tours. The moon is lovely. It will be delightful. How much to pay, dame? And a thousand thanks for your hospitality. Come, Marsillac,” and Ninon strode to the door. But the glimpses of the pillows within the shadow of the alcove had been too much for Marsillac, and he had already divested himself of his justaucorps, and jumped into bed.

“And now, my young gentleman, what about[12] you?” inquired Jacqueline of the embarrassed Ninon, who seated herself disconsolately on a little three-legged stool. “Come, quick, to bed with you!”

“No!” said Ninon, “I prefer this stool.”

“Oh, ta! ta! that will never do,” said Jacqueline, who was beginning to heap up a broad old settle with a cushion or two, and some wraps. “Sooner than that, I would sit on that stool myself all night, and give you up my place here beside my—Ah! à la bonne heure! There he is,” she cried, as the heavy footsteps of the master of the house, crunching up the garden path, amid the barking of the dogs, grew audible—“and, as I say, give you up my own place—”

“Ah, mon Dieu! no,” distractedly cried Ninon, tearing off her cloak; and bounding into the alcove, to the side of the already fast asleep Marsillac, she dragged the coverings over her head.

“Well, good-night! Sweet repose, you charming little couple,” laughed on Dame Jacqueline, as she drew the curtains to. “But I’d not go to sleep yet awhile, look you. Some friends of yours are coming here to see you. Ah yes, here they are! This way, ladies.”

And the next moment, Madame de Montaigu and the Duchesse de la Rochefoucauld stood within the alcove, gazing down with glances beyond power of words to describe.

Dragged by the two ladies from their refuge, Marsillac was hustled into his garments, but Ninon was bidden to leave hers alone, and to don the petticoats and bodice which the baroness had[13] brought for the purpose. “No more masquerading, if you please,” said her aunt, in tones terrible with indignation and severity, “while I have you under my charge. Now, quick, home with you!”

And home they were conducted, disconsolate, crestfallen, arriving there in an extraordinarily short space of time; for the château lay not half a league off, and the two runaways, who had imagined that the best part of Touraine had been covered by them that fine summer day, discovered that the mazes of the forest paths had merely led them round and about within hail of Loches, and Dame Jacqueline and her husband had at once recognised them. The man had then hastened immediately to the château, and informed the ladies, to their indescribable relief, about the two good-for-nothings; for the hue and cry after Mademoiselle Ninon and young Monsieur de la Rochefoucauld had grown to desperation as the sun westered lower and lower.

Ninon wept tears of chagrin and humiliation at the penalty she had to pay of being a girl again; but Marsillac’s spirits revived with astonishing rapidity. He even seemed to be glad at the idea of his fellow-scapegrace being merely one of the weaker and gentler sex, and in her dejection he was for ever seeking to console her. “I love you ever so much better this way, dear one,” he was constantly saying. “Ah, Ninon, you are beautiful as an angel!”

But alas! for the approach of Black Monday, and the holidays ended, Marsillac had to go back to school.

Troublesome Huguenots—Madame de L’Enclos—An Escapade, and Nurse Madeleine—Their Majesties—The Hôtel Bourgogne—The End of the Adventure—St Vincent de Paul and his Charities—Dying Paternal Counsel—Ninon’s New Home—Duelling—Richelieu and the Times.

The attack upon La Rochelle, and the incessant Huguenot disturbances generally, detained Monsieur de L’Enclos almost entirely away from Ninon, who remained at Loches in the care of her aunt. From time to time he paid flying visits to Loches—one stay, however, lasting many months, enforced by a severe wound he had received. This period he spent in continuing the instruction of his daughter, on the plan originally mapped out, of fitting her to shine in society. The course included philosophy, languages, music, with his special objections to the matrimonial state—engendered, or at least aggravated by his own failure in the search after happiness along that path. Far better, undesirable as he held the alternative, to be wedded to cloistered seclusion than any man’s bride; and well knowing Ninon’s horror of a nun’s life, he left her to argue out the rest for herself in her own logical fashion; and there is no doubt that the whole of her future was influenced by the views he then inculcated. A modest decorum and sobriety of bearing were indeed indispensable to good breeding; but carpe diem was the motto of Monsieur de[15] L’Enclos, as he desired it to be hers; and every pleasure afforded by this one life, certainly to be called ours, ought to be enjoyed while it lasted; and unswervingly, to the final page of her long record, Ninon carried out the comfortable doctrine.

At seventeen years of age, she was perfectly equipped. Beautiful and highly accomplished, amiable and winning, and though always well dressed, troubling vastly little over the petty fripperies and vanities ordinarily engrossing the female mind, she appears to have gained the commendation and affection of her aunt, who parted from her with great regret, when the failing health of Madame de L’Enclos necessitated Ninon’s departure from Loches, to go to Paris, where the invalid was residing.

Monsieur de L’Enclos fetched Ninon himself from Loches, and in a day or two she was by her mother’s couch. Madame de L’Enclos received her with affection, and affectionately Ninon tended her, going unmurmuringly through the old courses of religious reading and observance, even to renewing acquaintance with the gouty canon in Notre-Dame; but the invalid’s chamber was triste and monotonous, and now and again Ninon effected a few hours’ escape from it, ostensibly for the purpose of attending Mass or Benediction, or some service at one or other of the neighbouring churches. One of them, St Germain l’Auxerrois, was of special interest to Ninon, by reason of neighbouring the hotel of Madame de la Rochefoucauld; and she one day interrogated the guardian of the porte cochère, in[16] the hope of learning some news of Marsillac, whom Time’s chances and changes had entirely removed from her ken; but whose memory endured in her heart; for she had been very sincerely attached to him. The Suisse informing her that he very rarely came to Paris, the philosophical mind of Ninon soon turned for consolation elsewhere. On this plea of devout attendance at church, Ninon was freely permitted leave of absence from the sick room, duennaed by her old nurse, Madeleine, who, however, frequently permitted herself to be dropped by the way, at a small house of public entertainment, above whose door ran the following invitation to step inside:—

On one of these occasions, her charge went off in the company of a fairly good-looking and agreeable young gentleman who addressed her, as she halted for an instant at the corner of the Pont Neuf, in terms of mingled respect and admiration. Under his escort, she gathered some conception of the manners and mode of existence in the gay city, and in the course of their first walk together, they ran against two of her cavalier’s friends, who were to be associated intimately with her future—Gondi, the future Cardinal de Retz, and the young Abbé Scarron—Abbé by courtesy, since he never went beyond the introductory degree of an ecclesiastical career. In the company of these three merry[17] companions, she visited the Hôtel Bourgogne, a place which may be described as answering more to the music-halls, than to the theatres of the present time. Its frequenters could dine or sup at its tables, take a turn at tarot or thimblerig, and enjoy a variety entertainment carried out on lines mainly popular. It was a vast edifice, built in the Renaissance style, by Francis I., on the site of the gloomy, fortress-like mansion of Jean Sans Peur; and for a time it had been devoted to the representation of the Passion and Mystery plays, and the performances of the clerks of the Basoche, but grown decadent in these days of Louis XIII. Ninon obtained on her way a passing glimpse of His Majesty as he drove by, describing him “as a man of twenty-five; but looking much older, on account of his morose and taciturn expression, responding to the acclamations of the people only by a cold and ceremonious acknowledgment; while Anne of Austria, who followed in a coach preceded by other carriages, saluted the crowd with gracious smiles and wavings of her white hand.”

Having partaken of a light collation at one of the tables, the party gave attention for a while to the actors on the stage, whose performances were coarse, and not much to Ninon’s taste. Then Gondi and Scarron took leave of the two, and the sequel of the adventure proved a warning to young women endowed with any measure of self-respect, to refrain from making acquaintance with gallants in the street. Fortunately she escaped the too ardent attentions of the man, through the intervention[18] and protection of one of more delicacy and honour. Though this one was quickly equally enthralled, he went about his wooing of the beautiful girl in more circumspect fashion, a wooing nipped in the bud by his death from a wound received a short time later.

In the sombre calm of the invalid’s room stands out the grand figure of St Vincent de Paul, bringing to her, as to all the afflicted and heavy-laden, the message of Divine love and pity, and impressing Ninon with a lasting memory of reverence for the serene, pure face and gentle utterances of a heart filled with devotion for the Master he served. Never weary in well-doing, seeming ever to see God, his life was one long self-sacrifice and work of charity. Moved to such compassion for the poor convict of the galleys, who wept for the thought of his wife and children, that the good priest took the fetters from the man’s limbs, and bidding him go free and sin no more, wound them upon his own wrists: a heart so thrilled with love and sorrow for the lot of the miserable little forsaken children of the great city, that he did not rest till he had effected the reforms so sorely-needed for their protection.

Hitherto the small waifs and strays had been under the superintendence of the Archbishop of Paris. The charge of them was, however, delegated to venal nurses, who would frequently sell them for twenty sous each. On fête and red-letter days, it had for long been a custom to expose the little creatures on huge bedsteads chained to the pavement of Notre-Dame, in order to excite the pity[19] of the people, and draw money for their maintenance. St Vincent de Paul was stirred to the endeavour of putting a stop to these scandals; and instituted a hospital for the foundlings. It was situated by the Gate of St Victor, and the work of it was carried on by charitable ladies. The Hospital of Jesus, for eighty poor old men, was another of his good works; while he ministered to the lunatics of the Salpétrière, and to the lepers of St Lazare, within whose church walls he was laid to rest when at last he rendered up his life to the Master he had served; until the all-destroying Terror disturbed his remains: but “his works do follow him.” His compassion alone for the little ones will keep his memory green for all time.

Kneeling at his feet, at her mother’s bidding, the good priest bade Ninon rise, saying that to God alone the knee should be bent. Then he laid his hand on her head, calling down a benediction on her, and praying that she should be protected from the temptations of a sinful world. His words thrilled her powerfully for the time being. She felt moved to pour out all her heart to him, but “Satan,” she says, “held me fast, and would not let me approach God,” and the spell of the saintly man’s influence passed with his presence.

A few days later, Madame de L’Enclos died, calmly, and tended by her husband and her child, leaving at least affectionate respect for her memory. A year later, Monsieur de L’Enclos died. True to the last to his rule of life, the dying words he addressed to his daughter were these—

“My child, you see that all that remains to me in these last moments, is but the sad memory of pleasures that are past; I have possessed them but for a little while, and that is the one complaint I have to make of Nature. But alas! how useless are my regrets! You, my daughter, who will doubtless survive me for so many years, profit as quickly as you may of the precious time, and be ever less scrupulous in the number of your pleasures, than in your choice of them.”

The fortune of Mademoiselle de L’Enclos had been greatly diminished by the reckless extravagances of her father; and conscious, probably, of this error in himself, he was careful to protect her best interests, by purchasing for her an annuity which brought her 8,000 livres annual income. His prodigality was, however, one of the few of his characteristics she did not inherit. On the contrary, she displayed through life a conspicuous power of regulating the business sides of it with a prudence which enabled her to be generous to her friends in need, while not stinting herself, or the ordering of her households, and the entertainment of the company she delighted in; for the réunions and evenings of Mademoiselle de L’Enclos were a proverb for all that was at once charming and intellectual; varied as they were with sweet music, to which her own singing contributed—more notably still, by her performances on the lute, which were so skilful; though by these hangs the complaint that she ordinarily needed a great deal of pressing before she would indulge the company—a curious exception to[21] the ruling of the ways of Ninon, ordinarily so entirely innocent of affectation.

At this time her beauty and accomplishments, united with her fortune, drew many suitors for her hand, and of these there would probably have been many more, but for the certainty she made no secret of, that marriage was not in the picture of the life she had sketched out for herself. Her passion for liberty of thought and action in every aspect, fostered ever by her father, was dominant in her, and not to be sacrificed for the most brilliant matrimonial yoke.

One of her first proceedings was the establishment of a home for herself. It consisted of a handsome suite of rooms in the rue des Tournelles, in the quarter of the Marais, then one of the most fashionable in Paris, and distinguished for the many intellectual and gifted men and women congregating in the stately, red-bricked, lofty-roofed houses surrounding the planted space in whose centre, a little later, was to stand the equestrian statue of Louis XIII. The square had been planned by Mansard, and Ninon’s home—Number 23—had been occupied by the famous architect himself.

A few doors off was the residence of Cardinal Richelieu, and within the convenient distance of a few houses—Number 6—lived Marion Delorme. For years this Place Royale, as it is now called—at one time Place des Vosges—had been, until Mansard transformed it, held an accursed spot, and let go to ruin; for here it was stood the palace of the Tournelles, a favourite residence of Henri II., and in its courtyard took place the fatal encounter[22] between him and the Englishman Montgomery, whose lance pierced through the king’s eye, to his brain, and caused his death. Catherine de Médicis, in her grief and indignation at the tragic ending of that day’s tilt, caused the palace to be razed to the ground; but the old associations clung to the place, for it became the favourite spot for the countless duels which the young bloods and others were constantly engaging in; until Richelieu put an almost entire stop to them by his revival of the summary law against the practice, whose penalty was death by decapitation. The great cardinal’s ruling was not to be evaded, and several men of rank suffered death upon the scaffold for disobeying it.

Away beyond the St Antoine Gate at Picpus, Ninon established another dwelling for herself, in which it was her custom to rusticate during the autumn.

Beautiful—though in features not faultlessly so—she bore some resemblance to Anne of Austria, the adored of Buckingham, a likeness close enough to admit of the success of a freak played years later, when she contrived to deceive Louis the Great into the notion that the shade of his mother appeared to him, to chide him for certain evil ways. Her nose, like the queen’s, was large, and her beautiful teeth gleamed through lips somewhat full in their curves; her hair was dark and luxuriant, while her intelligent and sympathetic eyes expressed an indescribable mingling of reserve and voluptuous languor, magnetising all, coupled as it was with the charm of her gentle, courteous manner and conversation that sparkled with the wit and[23] sentiment of a mind enriched by careful training and study of the literature of her own time, and of the past. It was her crowning grace that she made no display of these really sterling acquirements, and entertained a wholesome detestation of the pedantry and précieuse taint of the learned ladies mocked at so mercilessly by that dear friend of hers, Molière. Few could boast a complexion so delicately fresh as hers. She stands sponsor to this day to toilette powders and cosmetics. Bloom and poudre de Ninon boxes find place on countless women’s dressing-tables to this hour; but in her own case art rendered little assistance, possibly none at all; except for one recipe she employed daily through her life. The secret of it, sufficiently transparent, was equally in the possession of the beautiful Diana of Poitiers, who also retained her beauty for such a length of years.

For all who list to read, her letter-writing powers stand perpetuated in her published correspondence, and while the theme is almost unvarying—the philosophy of love and friendship—her wit and fancy treat it in a thousand graceful ways. Fickle as she was in love, she was constant in friendship, and the heat of the first, often so startlingly transient, frequently settled down into life-long camaraderie rarely destroyed. While not ungenerous to her rivals in the tender passion, she could be dangerously jealous; but gifted with the saving grace of humour, of which women are said to be destitute, the anger and malice were oftentimes allowed to die down into forgiveness, and perhaps also, forgetfulness.[24] Rearing and temperament set Ninon de L’Enclos apart; even among those many notable women whose intimate she was. Essentially a product of her century, she lived her own life in its fulness. Following ever her father’s counsel, she was at once as boundlessly unrestricted in her observance of that perfect law of liberty to which she yielded obedience, as she was scrupulous in selection. Says Monsieur de St Evrémond of her—“Kindly and indulgent Nature has moulded the soul of Ninon from the voluptuousness of Epicurus and the virtue of Cato.”

And at last, after an interval of six years, Ninon and Marsillac met again. It was in the salon of the Hôtel de Rambouillet. Mademoiselle de L’Enclos, beautiful, sought after, already the centre of an admiring circle, the talk of Paris, and Monsieur le Capitaine de la Rochefoucauld, already for two or three years a gallant soldier, chivalrous, romantic, handsome with the beauty of intellect, interesting from his air of gentle, cynical pensiveness, ardent in the cause of the queen so mercilessly persecuted by Richelieu, and therefore lacking the advancement his qualities merited, still, however, finding opportunity to indulge in the gallantries of the society he so adorned. Someone has said that few ever less practically recognised the doctrines of Monsieur de la Rochefoucauld’s maxims, than did Monsieur de la Rochefoucauld himself, and the aphorisms have been criticised, and exception has again and again been taken to them, not perhaps altogether unreasonably; but in any case he justified himself of his dictum that “love[25] is the smallest part of gallantry”; for when at last—and it took some time—Marsillac recognised his old scapegrace chum of the Loches château, homage and admiration he yielded her indeed; but it was far from undivided, and shared in conspicuously by her rival, Marion Delorme, a woman of very different mould from Ninon. Like her, beautiful exceedingly, but more impulsive, softer-natured, more easily apt to give herself away and to regret later on. Intellectually greatly Ninon’s inferior, she was yet often a thorn in the side of the jealous Mademoiselle de L’Enclos.

To face page 24.

The times, as a great commentator has defined them, were indeed peculiar. The air, full of intrigue, was maintained by Richelieu at fever-heat, and wheel worked fast and furiously within wheel. There was the king’s party, though the king was little of it, or in it. The iron hand of the Cardinal Prime-Minister was upon the helm. Richelieu, who never stayed in resistance to the encroaching efforts of Spain—in his policy of crushing the feudal strength of the nobility of the provinces—or in annihilating Huguenot power as a political element in the State—saw in every man and woman not his violent partisan, an enemy to France and to the Crown. How far he was justified, how far he could have demanded “Is there not a cause?” stands an open question; but the effect was terrible. The relentless hounding down of the suspected, forms a page of history stained with the blood of noble and gallant men. Richelieu’s crafty playing with his marked victims, chills the soul. They were as ninepins in his hands, lured to[26] their destruction, sprung upon, crushed often when most they believed themselves secure.

Sending de Thou to the scaffold for his supposed complicity in the crime Richelieu fixed on Cinq-Mars, the handsome, insouciant, brilliant young fellow he had himself provided for the king’s amusement, and when the time was ripe, having done him to death by the Lyons headsman upon a superficially-based accusation. Richelieu was dying then. The consciousness of Death’s hand upon his harassed, worn-out frame was fully with him; but no pity was in his heart for Cinq-Mars. It might have been the old rankling jealousy that urged him on, for the stern, inflexible Armand de Richelieu was a poor, weak tool of a creature where women were concerned. “There is no such word as fail,” he was wont to say; yet in his relations with women, and in his gallantries he failed egregiously. No fear of him held back Marion Delorme from the arms of Cinq-Mars, when she yielded to his persuasions to fly with him; and self-love must have been bitterly wounded, when Anne of Austria laughed his advances to scorn. Richelieu was not a lady’s man. Nature had given him a brain rarely equalled, a stupendous capacity and penetration, but she had neglected him personally—meagre, sharp-featured, cadaverous, scantily furnished as to beard and moustache, and lean as to those red-stockinged legs. True, or the mere fruit of cruel scandal, that saraband pas seul he was said to have been duped into performing for the delectation of the queen, will hang ever by the memory of the great Lord Cardinal.

A Life-long Friend—St Evrémond’s Courtly Mot—Rabelais v. Petronius—Society and the Salons—The Golden Days—The Man in Black.

Scarcely was acquaintance renewed with her still quite youthful old friend, Monsieur de la Rochefoucauld, than Ninon met for the first time St Evrémond—Charles de St Denys, born 1613, at St Denys le Guast near Coutances in Normandy—the man with whom her name is so indissolubly connected, traversing nearly all the decades of the seventeenth century into the early years of the eighteenth, his span of life about equalling her own, and though for half of it absent from her and from his country, maintaining the links of their intimacy in their world-famed correspondence.

Like Ninon’s, his individuality was exceptional. A born wit, for even in his childhood, the soubriquet of “Esprit” was bestowed upon him, his three brothers being severally styled—“The Honest Man,” “The Soldier,” and “The Abbé.” Charles de St Evrémond was distinguished by a brilliant and singularly amiable intelligence. As a man of letters he was rarely gifted; though he evaded, more than sought, the celebrity attaching to the profession of literature, writing only, it may be truly said of him—

He never put forward his own works for publication, and it was only towards the close of his life that his consent was obtained for such publication. During his lifetime, many of his pieces in prose and in verse were printed and circulated in Paris and in London, where, at the Courts of Charles II. and of William III., forty years of his life were spent; but these were pirated productions, surreptitiously issued by his “friends,” to whom he occasionally confided his compositions, and they, for their own gain, sold them to the booksellers, who eagerly sought them. These pieces were altogether unfaithful to their originals, being altered to suit the particular sentiments of readers, and added to, in order to increase the bulk of the volumes. The style of St Evrémond’s writings has been the subject of encomium and warm appreciation from numerous learned critics and litterateurs, notably St Beuve and Dryden.

One contemporary editor, withholding his name, content with styling himself merely “A Person of Honour,” has, at all events, yielded due homage to St Evrémond’s character and genius. Commenting on the essays which have come within his ken, he writes—

“Their fineness of expression, delicacy of thought are united with the ease of a gentleman, the exactness of a scholar, and the good sense of a man of business. It is certain,” he adds, “that the author is thoroughly acquainted with the world, and has conversed with the best sort of men to be found in it.”

To this may be added the praise of Dryden—

“There is not only a justness in his conceptions, which is the foundation of good writing, but also a purity of language, and a beautiful turn of words, so little understood by modern writers.”

Agreeable, witty, an excellent conversationalist, and of real amiability of character and disposition, St Evrémond’s aim in life was to enjoy it. Indolently inclined, he accepted the ills and contrarieties of existence, finding even in them some soul of good. Always fond of animals, he surrounded himself in later years with cats and dogs, holding them eminently sympathetic and amusing; and he was wont to say that in order to divert the uneasinesses of old age, it was desirable to have before one’s eyes something alive and animated.

He possessed enough money for comfortable maintenance from several sources. Both Charles II. and William III. settled “gratifications” on him. His creed was a formless one, but he was no atheist, for all the charge of it laid to him. He was, on the contrary, quick to rebuke the profanity and laxity of mockers. He himself sums up his religion in these lines—

His writings were voluminous, flowing from his pen as a labour he delighted in. Their themes[30] were varied, brought from the rich stores of his mind, his most enduring and favourite subjects being classical Latin lore, and the drama of his own day, lustrous with great names in France, as in the country of his adoption.

Such, and much more, was St Evrémond the man of letters, and besides, he was a skilful and gallant soldier, distinguished for his brilliant sword-play, when he entered upon the exercises preparatory for his military career. In that capacity he won the approval and friendship of the Duke d’Enghien, fighting by the prince’s side at Rocroi and Nordlingen; though later a breach occurred in their relations, when St Evrémond indulged in some raillery at his expense. The great man vastly enjoyed persiflage of the sort where the shafts were levelled at others; but he brooked none of them aimed at himself, and St Evrémond was deprived of his lieutenancy.

Sometimes the wit carried a more flattering note, and once when disgrace shadowed him at Court for having appeared in the Sun-King’s presence in a pourpoint of a fashion not quite up to latest date, he said to His Majesty—“Sire, away from you, one is not merely unhappy: one also becomes ridiculous.” The conceit wiped away St Evrémond’s disfavour. He was a friend of several of the other renowned soldiers of his time, Turenne among them. It was one of Condé’s great delights to be read to by St Evrémond. The duke took pleasure in the lighter classics. Petronius had its attractions for him, as it had for[31] the society generally of the time; but he would have none of Rabelais, finding the grossness of the Curé of Meudon intensely distasteful, and refusing to listen to the adventures of Gargantua and Pantagruel and Grandgousier, and all their tribe, he insisted on the book being thrown aside. The merry romances of Petronius, or, at least, attributed to that “Elegantiæ Arbiter” of a pagan court, while ill adapted as milk for babes, as perhaps even for the more advanced in years, were not soiled with the lowermost grossness of the Christian man’s pen, and they were not without appeal to the students of the classic literature opened up by the Renaissance, even as the milder licence of Boccaccio charmed.

Truly, if the times were peculiar, it cannot be said of them that they were stagnant; and in movement and activity, the present century bears them some sort of comparison; though beyond this the parallel fails, to the winning of the days of Ninon. Autres temps, autres mœurs, and while there may be more veneer of morality in these present years of grace than then, the question remains whether the sense of it is deeper and more widely observed. It is one, however, outside the limits of these pages. Only that the aroma and delicacy of educated social intercourse do not permeate society as in that time is undoubted. Of course the impression existing in some minds of the widespread canker of profligacy and licentiousness then openly prevailing, is perverting of facts, since punctilio and the Court etiquette of the most punctilious of monarchs would not, and could not, have countenanced it.[32] Such licence was indulged in by, and confined, as it is now, to a certain section of the “smart” community, and this possibly no such narrow one; but at least it was veiled then by certain elements of good taste, and some womanly graces now far to seek. Not then, as now, the motor craze made existence uglier; then as not now, the bold, inane stares and painted faces of many of the gentler sex frequenting the highways and byways, were mostly screened by masks, and an awkward gait was mantled. Some cultivation of expression, and a little more sense, if not wit, graced the tongues now devoted to slang and the misuse of words which hang about the higher education; while the clamour of ill-advised women without doors was unknown. The comments of a recent French writer on the charm of life in those past days, are too valuable to be laid aside unrecorded. “The keen intellects of the time,” he writes, “caught a glimpse of everything, desired everything, and grasped eagerly at every new idea. Only those,” he goes on to say, quoting Talleyrand, “could realise the joy of being alive. The childish present-day philosophy of optimism and effort fails to lend life a charm it never knew before. The most insignificant gallant of the Court of Louis experienced more varied sensations than any rough-rider or industrial king has ever been able to procure for himself.” Admittedly, the evils of the time cried aloud for redress of wrongs which were all to be washed away later by the river of blood; but these had been more ameliorated than aggravated by the scholarship of thoughtful writers. Wit,[33] and the sense of beauty and delicacy of expression, carried, not unfrequently it is true, to affectations and absurdity, was the order of the day, binding men and women in links of an intellectual sympathy, whose pure gold was unalloyed by baser metal. Those réunions in the salons of the great ladies, must have been delightful, thronged as they were with distinguished men, and with women, many of them beautiful, spirituelle, or both. But for the sparkle of true wit, the music of sweet voices, the ripple of verse and epigram, the popularity of those gatherings would not have been so long maintained. The atmosphere of them was sweet with the lighter learning of old Rome and Greece, and the gaiety of graceful modern rhymes, or the sentiment of the latest sonnet. The passing of centuries had now left far behind the barbaric clash of warfare, and widened the old limitations of mediævalism and Scholasticism. From the hour the cruel knife of Ravaillac stilled the noble heart of the great Henri, the times had ripened to the harvest of a literature resplendent with promise of illustrious names.

Ever zealous for the glory of France, Richelieu founded the Académie Française; and later the college of the Sorbonne, where now he lies magnificently entombed, was rebuilt by him, and devoted to its old purpose of a centre of learning; and as of old, and as ever, men thronged from near and from afar to Paris for the study of art and learning, and to pay such homage to the modern Muses and enjoy their smiles, as good fortune might allow.

Amid such environment it was, that Ninon embarked upon the stream of the life she had elected to follow, hoping to pass, as indeed she did, through the years serenely and in fair content. If now and again some minor questions of spirit troubled her—conscience it could scarcely be called, since by the lights she had chosen to guide her, conscience could hardly be reproachful—it was but passingly. Yet the tale goes of the visits of a Man in Black, a most mysterious personage, who at his first interview, when she was about eighteen years old, brought her a phial containing a rose-coloured liquid, of which a little, a mere drop, went a very long way. It was the recipe for prolonged youthfulness, and certainly must have been very efficacious. It was, he said, to be mixed with a great deal of pure water, quite as much as a good-sized bath would contain—and a bath of pure water is, of course, in itself a very healthful sort of thing. Many a year went by before the Man in Black—or one so like him as to be his very double—came again, and Ninon was prone to shrink at the remembrance of him. When he did come, it was to inform her that some years of this life still lay before her; and then for the third time that Man in Black presented himself, and—But the cry is a far one to seventy years hence, and during that time, as far as Ninon was concerned, he remained in his own place, wherever that might be; and if, after all, he had been but a dream, in any case the shadow of his sable garb does not appear to have been very constantly cast upon the mirror of her existence.[35] That was bright with love and friendship, the love and friendship of both sexes, and truly if in love she was frankly fickle à merveille, in friendship she was constant and unchanging. Ever following the dying parental counsel, she was fastidious in the choice of the aspirants to her favours. In her relations with women and men alike, honest and honourable and full of a kindly charm which made her exceptionally bonne camarade. It was small wonder that the salon of Mademoiselle Ninon de L’Enclos was a centre of foregathering greatly sought after.

A “Delicious Person”—Voiture’s Jealousy—A Tardy Recognition—Coward Conscience—A Protestant Pope—The Hôtel de Rambouillet—St Evrémond—The Duel—Nurse Madeleine—Cloistral Seclusion and Jacques Callot—“Merry Companions Every One”—and One in Particular.

Six years had passed since as girl and boy Ninon and Marsillac had parted at Loches. At sixteen years old he had entered the army, and was now Monsieur le Capitaine de la Rochefoucauld, returned to Paris invalided by a serious wound received in the Valtellina warfare. Handsome, with somewhat pensive, intellectual features, chivalrous and amiable, he was “a very parfite gentle knight,” devoted to the service of the queen, which sorely interfered with his military promotion: devotion to Anne of Austria was ever to meet the hatred of the cardinal, and to live therefore in peril of life.

The daring young hoyden of Loches was now a graceful, greatly admired woman of the world, welcomed and courted in the ranks of the society to which her birth entitled her.

It was quite possible that the change in her appearance was sufficiently great to warrant de la Rochefoucauld’s failure to recognise her in the salon of Madame de Rambouillet when he passed her, seated beside her chaperon, the Duchesse de la Ferté—not, however, without marking her beauty; and he inquired of the man with whom he was walking[37] who the “delicious person” was. The gentleman did not know. It was the first time, he believed, that the lady had been seen in the brilliant company. The impressionable young prince lost little time in securing himself an introduction, further economising it by expressing his sentiments of admiration so ardently, that they touched on a passionate and tender declaration. Ninon accepted this with the equanimity distinguishing her; she was already accustomed to a pronounced homage very thinly veiled. It was to her as the sunshine is to the birds of the air, almost indispensable; but she found the avowals of his sentiments slightly disturbing in the reflection that Marsillac had altogether forgotten his Ninon. That, in fact, he had done long since. The fidelity of de la Rochefoucauld in those days, was scarcely to be reckoned on even by hours. Already he was in the toils of Ninon’s beautiful rival, Marion Delorme, a woman Ninon herself describes as “adorably lovely.” Beauty apart, the very antithesis of Mademoiselle de L’Enclos, weaker of will, more pliably moulded, warm-hearted, impulsive, romantically natured, apt to be drawn into scrapes and mistakes which Ninon was astute enough rarely to encounter. The two women lived within a stone’s throw of each other, and it needed hardly the gossip of the place for Ninon to observe that Marsillac was but one more of the vast company of arch-deceivers. It was Voiture, the poet and renowned reformer of the French tongue, who hinted the fact to Ninon with, no doubt, all his wonted grace of expression,[38] further inspired by jealousy of the handsome young captain, that at the very moment he was speaking, de la Rochefoucauld was spending the afternoon in Marion’s company, en tête-à-tête.

Thereupon, linking her arm in Voiture’s, Ninon begged him to conduct her to Number 6, rue des Tournelles. The poet, vastly enjoying the excitement his words had evoked, readily complied, and arrived at Marion’s apartments where the Capitaine de la Rochefoucauld was duly discovered. Then broke the storm, ending in Marsillac’s amazement when Ninon demanded how it was that he had not discovered in her his old friend Ninon de L’Enclos. Then, in the joy and delight of recognition, Marsillac, forgetting the very presence of her rival, sprang to her side, and offering her his arm, sallied forth back to Ninon’s abode, spending the rest of the day in recalling old times at Loches, and in transports of happiness. Only late into the night, long after Marsillac had left her presence and she was lost in dreamful sleep, it brought the faces of her mother and of St Vincent de Paul vividly before her, gazing with sad reproachful eyes; and with her facile pen she recorded the memory of that day, fraught with its conflict of spirit and desire.

“O sweet emotions of love! blessed fusion of souls! ineffable joys that descend upon us from Heaven! Why is it that you are united to the troubles of the senses, and that at the bottom of the cup of such delight remorse is found?”

Whether through the silence of the small hours any echoes touched her vivid imagination of the[39] Man in Black’s mocking laughter, no record tells; but in any case, with the fading of the visions, the disturbing reflections were quickly lost in the joy of Marsillac’s society, as also in that of St Evrémond—the very soul of gaiety and wit and every delightful characteristic.

says Captain MacHeath, and there were days together that Marsillac did absent himself. The grand passion of his life was not with either of the two women, or with any of the fair dames then immediately around. They were merely the toys of his gallant and amiable nature, and at that time he was deeply absorbed in the duties of his profession, and his ardent devotion to the queen’s cause. It was, indeed, one most difficult and dangerous, ever facing, as it did, the opposition of Richelieu, who saw in every friend and partisan of Anne of Austria Spanish aggression and a foe to France.

Some cause there surely was. Political and religious strife raged fast and hotly. From the outset—that is, at least, as far back as the time when the Calvinists banded together to resist the Catholics—it was not a question alone of reform or of change in religious conviction. It could not have remained at that: the whole framework of government would have been shaken to its foundation had the Reformed party ultimately triumphed; but the passing of a century had wrought startling changes.[40] There were many of the Catholic nobility whose policy was as much to side with the Huguenot party, as it had been the wisdom of the Protestant Henri IV. to adopt the Catholic creed. Richelieu, in conquering Rochelle, showed the vanquished Huguenots so much leniency, that public clamour nicknamed him “the Cardinal of Rochelle,” and “the Protestant Pope,” and he laughed, and said that there was more such scandal ahead; since he intended to achieve a marriage between the king’s sister, Henrietta Maria, and the non-Roman Catholic king, Charles I. of England.

To hedge his country from the encroachment of Spain was the life-long aim and endeavour of Richelieu, and he was ruthless in the means. The eastern and northern frontiers of France were constantly menaced and invaded by Austria and Spain and their allies, and to and fro to Paris came the great captains and soldiers engaged in the constant warfare against the enemy—men of long lineage, brave, skilful in arms, dauntless in action, and certainly no laggards in love when opportunity afforded; and they returned loaded with honour, covered with glory, and often seriously wounded, to be welcomed and made much of in the salons of noble and titled women, like the Duchesse de Rambouillet, and other réunions scarcely less celebrated and brilliant, where the fine art of wit, and the culte of poetry and belles-lettres, mingled with a vast amount of love-making, and at least as much exquisite imitation of it, were assiduously conducted. It was the hall-mark of good society, a virtue[41] indispensable, and to be assumed if it did not really exist, and too greatly valued for other virtues to be set great store by. So that the line of demarcation between women of unimpeachable repute, and those following a wider primrose path grew to be so very thinly defined as sometimes to be invisible and disregarded. Notably in the refined and elegant salon of Ninon de L’Enclos were to be counted many ladies of distinction and modes of life untouched by the faintest breath of scandal, who loved her and sought her friendship, as there were men who were quite content to worship from afar, and to hold themselves her friends pure and simple to life’s end.

Who of her admirers was the first winner of the smiles of a more tender intimacy, is not more than surmise, remaining recorded only in invisible ink in a lettre de cachet whose seal is intact. If the friend of her early girlhood at Loches is indicated, it may be intentionally misleading. Count Coligny was an acquaintance at whose coming Ninon’s bright eyes acquired yet greater lustre, and de la Rouchefoucauld’s reappearance had not yet taken place—“ce cher Marsillac,” whose devotion, even while it lasted, was tinctured with divided homage, and was to dissolve altogether, in the way of love sentiments, in the sunshine of his deep undying attachment to Madame de Longueville. There was, however, no rupture in this connection; the burden of the old song was simply reversed, and if first Marsillac came for love, it was in friendship that he and Ninon parted, giving[42] place to the adoration of St Evrémond—bonds which were never broken, and whose warm sentiments the waters of the English Channel, flowing between for forty years, could not efface. The effect might have been even the contrary one, and absence made the heart grow fonder, though the temperaments of Ninon and of St Evrémond were undoubtedly generously free of any petty malignance and small jealousies.

Monsieur de L’Enclos had survived his wife only by one year. He died of a wound received in an encounter arising from a private quarrel. Had he recovered, it would probably have been to lose his head by the axe, paying the penalty of the law for some years past rigorously enforced against duelling. The scene of such encounter being most frequently the open space of the Place Royale, the locality of the cardinal’s own house—as it was of Ninon and of Marion Delorme—so that his stern eyes were constantly reminded of the murderous conflicts. The law, having been enacted by Henri IV., had fallen into abeyance, until the specially sanguinary duel between the Comte de Bussy and the Comte de Bouteville, in 1622, when de Bouteville mortally wounded de Bussy, and Richelieu inflicted the penalty of decapitation on de Bouteville and on Rosmadec his second, as he did on others who disobeyed; so that the evil was scotched almost to stamping out. It was in this fashion that Richelieu made his power felt among the nobility and wealthier classes, and let it be understood that the law was the law for all.

Almost immediately following on the death of Monsieur de L’Enclos, came that of Ninon’s old nurse, Madeleine—whose kind soul and devoted attachment were in no wise ill-affected by the small nips of eau de vie she inclined to—and just about the same time died Madame de Montaigu, her aunt at Loches; and thus within six months she had lost the few of her nearest and dearest from childhood, and she felt so saddened and desolate and heart-broken, that she formed the resolution of giving up the world and being a nun after all—yearning for the consolation which religion promises of reunion, and a fulness of sympathy not to be found in ordinary and everyday environments! Scarcely as yet with her foot on womanhood’s bank of the river of life, the warm kindly nature of Ninon was chilled and dulled by sorrow and regret; and one evening, at the Hôtel de Rambouillet, in her ardent desire to find some peace and rest of spirit, she entered into conversation with the Père d’Orléans, a renowned Jesuit, on the subject of religious belief—but his best eloquence failed in convincing her of its efficacy.

The right of private judgment, ever one of her strongest characteristics, asserted itself, and she declared herself unconvinced. “Then, mademoiselle,” said the ecclesiastic, “until you find conviction, offer Heaven your incredulity.”

But while words failed, her heart still impelled her to the idea of the cloistered life, and she went to seek it in Lorraine, at a convent of Recollettes sisters near Nancy. There were many houses of[44] this Order in the duchy. The one sought entrance to by Ninon, was under the patronage of St Francis, and she was received with effusion by the Reverend Mother, a charming lady, herself still youthful. She had not, however, been there many days, relegated to a small cell, whose diminutive casement looked upon some immediately-facing houses, before she became impressed with the idea that, great as the desire might be to snatch in her a brand from the consuming of the wicked world, it was greater still for the little fortune she was known to possess; and with the passing of time, the gentle assuager of more poignant grief, she was beginning to feel less attracted towards the conventual mode of existence, and to wonder whether she really had the vocation for it. Meantime, the old spirit of adventure was strongly stirring her to defer the recital of a formidable list of Aves and penitential psalms, in favour of watching a window facing her loophole of a lattice, through which she could see a man busily engaged with burin and etching implements. While this in itself was not uninteresting, the interest was increased tenfold, when she contrived to discover that he was the already famous Jacques Callot, the engraver; and very little time was lost before the two had established means of communication by the aid of a long pole, to which they tied their manuscript interchange of messages and ideas—which culminated in Ninon’s descent by a ladder of ropes from the lattice, and flight from the convent.

More sober chronicles relate of Jacques Callot,[45] that through all the curious vicissitudes and adventures of his earlier life, he remained blameless and of uncorrupted morality. It appears certain that his real inclination was ever for such paths, and the romantic love-affair which ended in his union with the woman he adored, was calculated to keep him in them; in which case the attributed version of his liaison with Ninon must be accepted with something over and above its grain of salt, and allowed to lie by. That he was a fearless, high-minded man, as well as a great artist, stands by his honoured name in a golden record; for when the imbroglio occurred between Louis XIII. and the Duke of Lorraine—in which, under the all-conquering cardinal prime-minister, France was the victor—Callot was commanded to commemorate the siege with his pencil—he refused. Callot was a Lorrainer, and the duke was his patron and liege-lord, and Callot refused to turn traitor, and prostitute his gift by recording the defeat of the duke, preferring to run the very close chance of death for high treason sooner than comply. If, as it is asserted, Ninon obtained for him the pardon of Richelieu, by virtue of some former favour or service she had done the cardinal, leaving him as yet in her debt for it, all was well that so well ended; and it adds one more to the list of Ninon’s generous acts, never neglected where she had the power to perform them for those she loved.